Alternative State

Alternative State

Hawaii has become an incubator for all sorts of renewable-energy

projects

By JIM CARLTON

June 30, 2008

HONOLULU — A state better known for sun and fun is quietly

morphing into one of the world’s leading incubators of alternative

energy.

Royal Dutch Shell PLC is heading up a test venture in Hawaii to

turn oil-rich algae into fuel. If the process is found commercially

viable, the Anglo-Dutch conglomerate could build algae-

processing plants elsewhere.

THE JOURNAL REPORT

Ever-Green Energy LLC of St. Paul, Minn., plans to build a plant

in Honolulu that uses seawater to cool office buildings; if

successful, the project will be expanded to other states. A start-up

company, meanwhile, is deploying miniature solar-thermal

collectors on Oahu to help generate more power for the local

electricity grid. This set-up, too, if successful, will be reproduced

elsewhere.

The reason for all the interest: location, location, location.

“Hawaii is the only place in the world where you have access to

every form of renewable energy, and you are on the dollar and

the U.S. legal system,” says Joelle Simonpietri, a former venture

capitalist who now heads an algae-to-fuel firm called Kuehnle

AgroSystems Inc.

Hawaii is trying to convert to clean energy as fast as it can.

Petroleum imports make up about 80% of the energy supply for

Hawaii’s main utility, leaving the state among those hardest hit by

the run-up in oil prices. Electricity rates have gone through the

roof. The average residential rate on Oahu, where most of

Hawaii’s 1.2 million residents live, had doubled to 25.50 cents a

kilowatt hour — the highest in the U.S. — from 12.74 cents in 1999,

according to Hawaiian Electric Co., the state’s major utility.

So, in January, Gov. Linda Lingle announced plans under a state-

federal partnership for Hawaii to derive 70% of its energy from

renewable sources by 2030 — one of the most ambitious targets

in the world.

Ormat Technologies’ geothermal plant in Puna

The state has gotten a head start toward this goal in some places.

On Maui, for example, wind farms power 11,000 homes, or about

10% of that island’s energy, while on the Big Island, which is

Hawaii itself, geothermal power from volcanic vents accounts for

about a fifth of the energy there.

And on Oahu, Hawaiian Electric is building a new power plant that

will generate 110 megawatts — enough power for about 30,000

homes — and will run completely on biodiesel fuel. The $160

million plant, expected to open next year, will initially get its fuel

from imported palm oil.

“Everything is possible as oil prices rise,” says Henry

Montgomery, chief executive of MontPac Outsourcing, a finance

and accounting consultancy in Honolulu.

Not all the technologies are problem free. Environmentalists want

to make sure, for example, that Hawaiian Electric doesn’t import

any of its palm oil from endangered rainforests in Asia. Utility

officials say that their palm oil will come from sustainable sources,

and that over time the plant will rely more on crops grown in

Hawaii.

There’s also a question of whether the sources of energy can

overcome technical hurdles, among other challenges.

Gov. Lingle, for her part, says Hawaii is counting on a multitude of

the clean-energy technologies to succeed — not any particular

one. “If our experience with petroleum has taught us anything, it is

not to get reliant on any one source of energy,” the governor said

in a recent interview at her state capital office, where, moments

earlier, the power went down due to a temporary malfunction.

Here is a sampling of what’s going on in Hawaii:

SOLAR

One of Hawaii’s most abundant resources is its sunshine. But like

many places, solar power used to cost so much more than

conventional power it largely wasn’t economical — until oil prices

got so high.

Now, several solar companies in Hawaii are trying to cash in on

the boom in clean-energy demand. Hoku Scientific Inc. until last

year specialized in making fuel cells. Now the Honolulu company

makes silicon for photovoltaic solar cells at a factory in Idaho,

while in Hawaii it installs solar panels for mostly corporate

customers including the Bank of Hawaii and Hawaiian Electric.

“Obviously, with the high electric rates, Hawaii is a great place to

sell alternative energy,” says Darryl Nakamoto, Hoku’s chief

financial officer.

Another company, Sopogy Inc., is augmenting local power with

solar-thermal energy, a technology that uses mirrors and lenses

to concentrate the sun’s rays on fluids, creating steam that turns

turbines to generate electricity. Spun off last year from a

technology company called Energy Industries, Sopogy has

created a miniature version of the giant solar collectors found in

places like the California desert. “Micro” collectors weigh about

100 pounds, measure 12 feet by five feet, and can be deployed

on building rooftops, Sopogy officials say. Also, unlike many

technologies that tap the sun, Sopogy has designed its system so

it can store solar energy, the company says.

Last year, Sopogy got $10 million in state revenue bonds to set

up a one-megawatt demonstration farm on Hawaii. In May, the

state Legislature approved $35 million in bonds to help Sopogy

build a solar plant on Oahu that will generate 10 megawatts, or

enough power for about 3,000 homes, for Hawaiian Electric.

Privately held Sopogy has raised more than $10 million in other

money as well, including from Kolohala Ventures, a Honolulu

venture-capital firm.

If successful, Sopogy hopes to expand its micro solar plants

around the world. “We want to see our revenues at $1 billion in

five years,” says Darren Kimura, president and chief executive of

Sopogy, and founder of Energy Industries.

ALGAE

One of the holy grails in alternative energy is a system that can

extrude oil from algae on a grand, and economical, scale.

Scientists say oil represents as much as half the body weight of

algae, compared with about 20% for corn, one of the most widely

used biofuel crops. Algae also grows as much as 10 times faster

than corn, and can be processed for oil without disrupting food

supplies.

However, the technical challenges have proven large in the past.

For example, studies have shown algae strains that can produce

the most energy often need to be starved of nutrients, which

stunts their growth. Indeed, some previous efforts in the U.S. and

Japan over the past 30 years have been dropped, in part,

because costs were exorbitant.

But now that oil is so high, several companies are turning to algae

again. One of the more closely watched is Cellana, a Shell-led

venture with a University of Hawaii spin-off, HR Biopetroleum.

The companies announced in November 2007 that the venture

would build a pilot facility on the Big Island’s Kona coast. Since

then, researchers have been busy planting various strains of

algae in test tubes that sit in the warm sea water on the Kona

coast. One of the tasks facing them is to find algae that both

contains the highest amounts of oil and can grow in warm water.

“We’re in the process of whittling down the top super bugs from

hundreds to 10,” says Susan Brown, a University of Hawaii

researcher who collects specimens for the project on scuba dives

around local waters.

SEAWATER

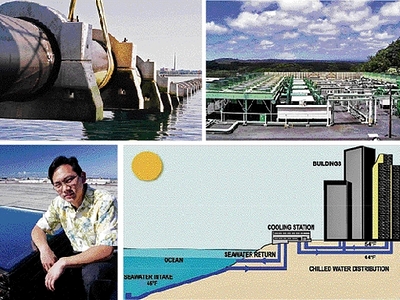

One of the simplest clean-energy concepts is to take cool water

from the ocean or a lake and use it to help air-condition buildings

in nearby cities. The technique has been used in places like

Amsterdam and Toronto, with significant power savings.

But piping water to where it needs to go requires more capital

investment than many places were willing to make when oil was

cheaper. Until recent years, there were also limitations on how

deep pipes could be put to suck up the colder water.

In 2003, David Rezachek — a former manager of Hawaii’s

alternative energy program — held a workshop in Honolulu to

revive local interest in seawater air-conditioning. Even then,

Hawaii’s electric rates were the highest in the country. “I said, ‘It’s

time to quit talking about it, let’s do this thing,’” Mr. Rezachek

recalls.

He helped get Ever-Green Energy — then called Market Street

Energy — to set up a subsidiary called Honolulu Seawater Air

Conditioning. The company invested about $3.5 million in the

venture, while $10.8 million has been raised from mainland and

Hawaiian investors, including Kolohala Ventures, says Mr.

Rezachek, associate development director for Honolulu

Seawater. The state Legislature has also authorized $100 million

in tax-exempt revenue bonds for a seawater cooling project.

The venture proposed in late 2003 a seawater cooling project be

built for downtown Honolulu. Although ocean temperatures on the

beaches around Oahu hover in the mid 70s, they drop to 45

degrees at 1,600 feet deep a few miles offshore. So Honolulu

Seawater proposed to run a pipe from 1,600 feet deep to a

cooling plant onshore, four miles away. The cold seawater would

pass through a heat exchanger where it would cool fresh water

from separate pipes used to chill nearby office towers downtown.

Designed to cool 12.5 million square feet of office space — or the

equivalent of almost five Empire State Buildings — the Honolulu

system is projected to save as much as 15 megawatts of

conventional power, while at the same time cutting greenhouse

gas emissions by 84,000 tons a year. The venture expects to

secure permitting by early next year, and be in operation in 2010

at a cost of about $165 million.

GEOTHERMAL

Few places in the world have as much geothermal energy

potential as Hawaii’s Big Island, where the Kilauea volcano has

been erupting since 1983. As long ago as 1881, Hawaiian King

David Kalakaua met with inventor Thomas Edison to discuss

harnessing the power of Hawaii’s volcanoes.

In the 1970s, a public-private partnership dug the first geothermal

well in Puna on the windy east side of the island. Over time,

enough hot water and steam was taken out of the ground to fuel a

30-megawatt power plant. The plant, owned by Reno, Nev.-based

Ormat Technologies Inc., provides power to about 10,000 homes,

or 18% of the Big Island’s total supply, according to Hawaiian

Electric.

Conceivably, the Kilauea volcano could provide enough power to

meet all of Hawaii’s needs, state utility officials say. But there are

several limitations. One is the Big Island’s isolation from the other

Hawaiian islands. For example, the ocean is so deep between it

and the next closest island, Maui, that officials in the state

abandoned a past plan to try and lay an underwater cable

between the islands to transfer the geothermal energy.

Another issue: opposition to significant expansion of geothermal

by some native Hawaiians, on grounds the volcano is sacred,

says Robert Alm, a spokesman for Hawaiian Electric.

–Mr. Carlton is a staff reporter in the San Francisco bureau of

The Wall Street Journal.